Russian Attack on Kyiv TV Tower

We analyze the Russian missile strikes on the Kyiv TV Tower in three dimensions, placing them in direct relation to the adjacent site of Babyn Yar. By mapping historical and modern attacks side by side, this investigation highlights the continuity and impact of conflict in this area.

On 1 March 2022, Russia launched a missile strike on the Kyiv TV tower. It was not particularly effective militarily, nor was it among the deadliest strikes in Russia’s attack on Ukraine. However, the significance of targeting the capital city’s main television and radio tower cannot be underestimated, especially in a war that is as much about control over narrative as over land and the people inhabiting it.

The missiles targeting the TV tower landed on the territory known as Babyn Yar, the site of one of the worst massacres of the Holocaust. Historical references, particularly ones related to the Second World War and the Holocaust, have been continuously weaponised as part of Russia’s propaganda machine. Given their claims about the ‘de-Nazification’ of Ukraine, the damaging of one of the Holocaust’s most significant symbols, is particularly ironic.

Our investigation seeks to examine the confluence of past and present in this fraught landscape, drawing together a detailed analysis of the recent strike on the TV tower and a spatial reconstruction of the Babyn Yar site—a complex ravine system that used to run through this part of Kyiv. By excavating the historical layers of the Babyn Yar site, we have been able to locate within it the massacres that took place and the multiple attempts made to silence their memory.

First missile

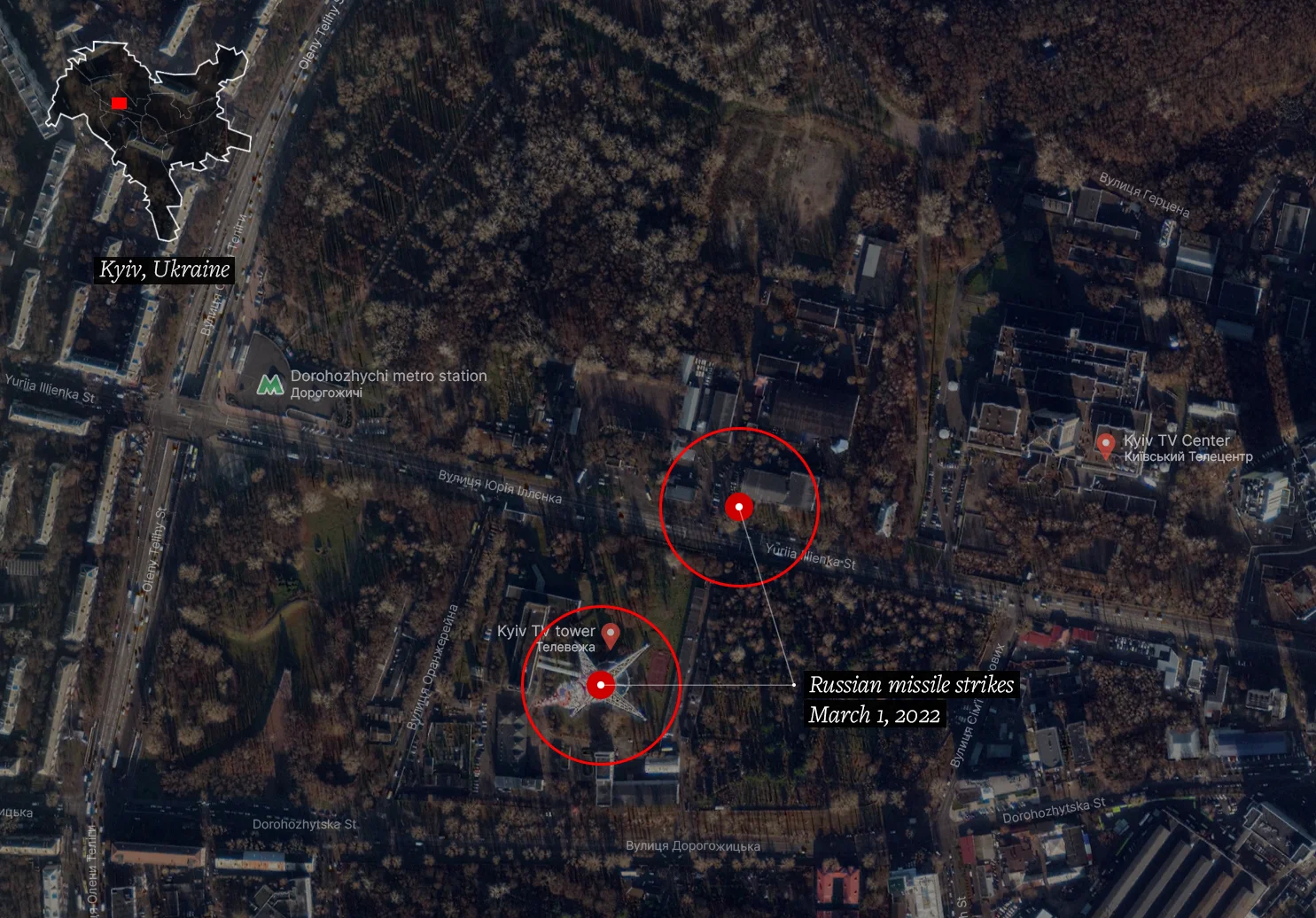

Shortly after 5 pm on 1 March, a missile hit the capital’s main radio and TV tower, exploding just below the control room. It was captured on video in mid-flight by numerous sources. Using these videos, we were able to calculate the size of the projectile relative to the tower, and through consultation with munitions specialists concluded that it was likely to be an air-launched cruise missile, such as the 3M-54 Kalibr. We then synchronised multiple videos of the attacks by comparing the light and smoke plume from the explosion, which allowed us to determine the exact time of the first strike to be 17:08 EET. The TV tower withstood this first explosion. According to media outlet France 24, most channels hosted in the tower were back on the air about an hour after the strike. A nearby building caught on fire.

Second missile

At 17:19, a second strike followed, passing close to the TV tower, seemingly missing it, and landing close to a Soviet-era building 200 metres away from the tower, across Illienka Street. The building, which is part of the Avangard Sports Complex, sustained significant structural damage. This structure had been due for renovation by the Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Center to host the new Museum of Holocaust in Ukraine and Eastern Europe. The Ukrainian police confirmed that Yevhenii Sakun, who worked for the media channel LIVE TV, was killed along with four others. Five more people were wounded.

Attacks on civilian communication infrastructure

The Kyiv TV tower was reportedly used by a wide range of civilian TV and radio stations such as public TV channel UA Pershiy, the privately-owned TV channel 1+1, and the news channel Ukraine 24. At 385 metres high, the tower is the tallest structure in Ukraine and the tallest free-standing lattice structure in the world. It was designed by Kyiv-based V.N. Shimanovsky Ukrainian Institute of Steel Construction and erected in 1973.

Due to the unique upbuilding method used in its construction and its monumental height, it is included in The State Register of Monuments of Ukraine, which designates it a landmark with cultural heritage status.

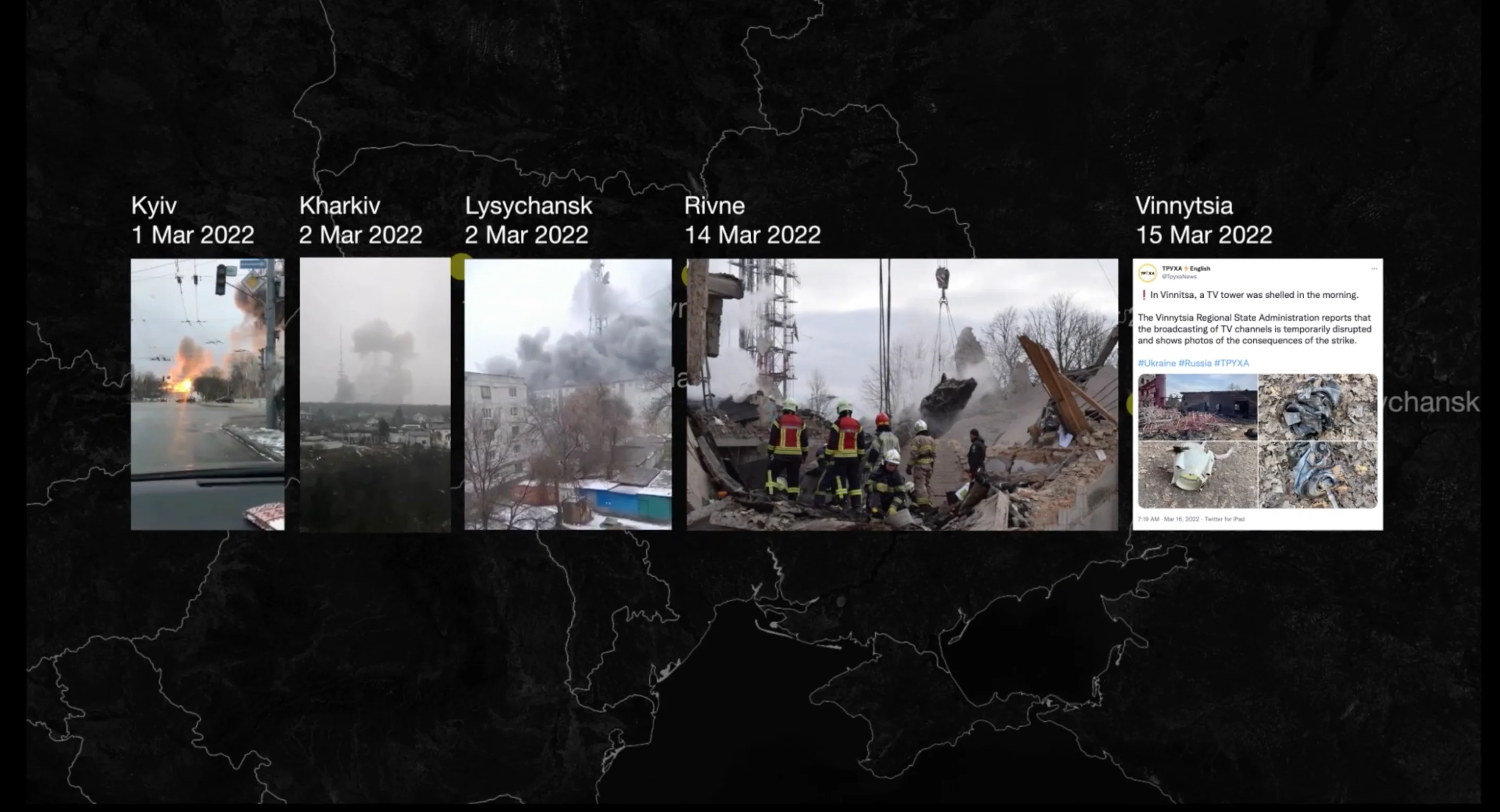

The Ukrainian NGO Institute for Mass Information recorded at least ten Russian attacks on TV towers throughout Ukraine between 24 February and 24 March. TV towers in Kharkiv and Lysychansk were hit on 2 March, the day following the attacks in Kyiv, and further towers were targeted on 14 March in Rivne and on 15 March in Vinnytsia. In total, at least 32 TV channels and several dozen radio stations were affected over a one month period.

According to the Berlin-based European Center for Constitutional Human Rights (ECCHR), these systematic raids on the civilian communication infrastructure in Ukraine point to the Russian armed forces’ objective to disrupt the spread of information and demoralise the population.

On Tuesday, 1 March 2022, five days before the strike on the Kyiv TV tower, the Russian Defence Ministry warned that it planned to strike technological objects in Kyiv to prevent ‘informational attacks’ against Russia.

There is no evidence to indicate that the damaged TV tower and adjoining technical buildings were being used for any military objectives. In its assessment of the attack, ECCHR confirmed that the TV tower was neither a military object nor a dual-use object, meaning that there was no lawful basis for the Russians to target it.

The open admission from the Russian Defence Ministry that forthcoming strikes were intended to thwart ‘informational attacks’, and the subsequent enactment of these threats through a pattern of attacks against civilian communications infrastructure, makes evident that the ECCHR’s assessment was correct, and reveals Russia’s strategic focus on supporting its disinformation efforts by attempting to eliminate voices that contradict its messaging.

As to the legitimacy of this defense, examining relevant legal precedents, ECCHR reviewed the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY)’s legal opinion regarding the NATO strike in 1999 on Belgrade’s Avala tower — another culturally significant TV tower, which supported the operation of Serbian TV and radio channels. In their statement, the ICTY insisted that ‘civilians, civilian objects, and civilian morale as such are not legitimate military objectives’. The ICTY also stressed that although the media may disseminate propaganda, this does not make its operations a legitimate military target.

Historical strata

The illegal nature of a strike on a communication tower is compounded by the fact that both the tower itself and the site on which it stands are sites of cultural heritage.

The strike on the TV tower and Babyn Yar territory has led to condemnation from political figures all over the world, including President Zelensky, who tweeted that it negated the post-Second World War promise ‘never again’.

The strike aimed at the Ukrainian media networks hit a tangled nervous system of historical references and repressed memories. Both missiles landed in close proximity to what used to be Babyn Yar ravine (‘yar’ is a ravine in Ukrainian and Russian).

Like needle probes, these missiles pierced through layers of historical strata, resulting in a spatial and temporal collision between the events of the current war and the site's deeply rooted history.

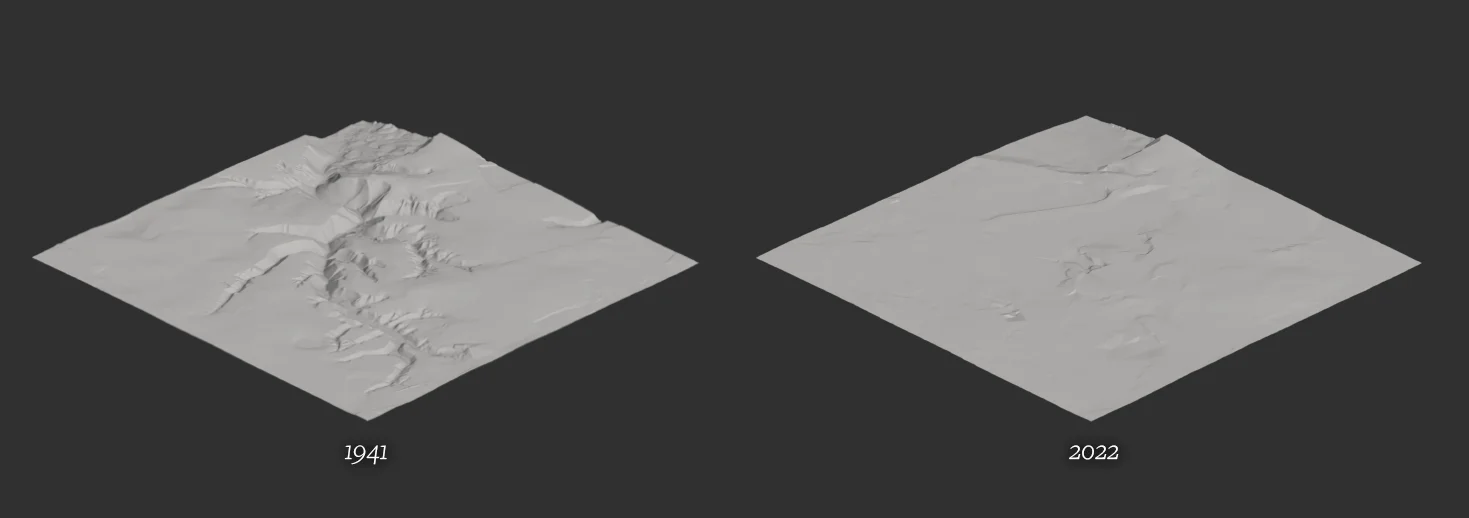

Between 15 February 2020 and 24 February 2022, The Center for Spatial Technologies undertook a commission from the Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Center to spatially investigate and digitally reconstruct the original topography of the Babyn Yar site.

Because both the genocide and its cover-up altered the topographical feature of the ravine, CST’s investigation afforded special attention to precisely modeling the landscape of the site across different periods in its history.

The landscape model was built by drawing from a combination of old topographic maps from the early 20th century, aerial images, and archival photographs that offered information about distinct features of the terrain from the beginning of the 20th century until the site was filled in and smoothed over in the 1950s.

Reading the landscape

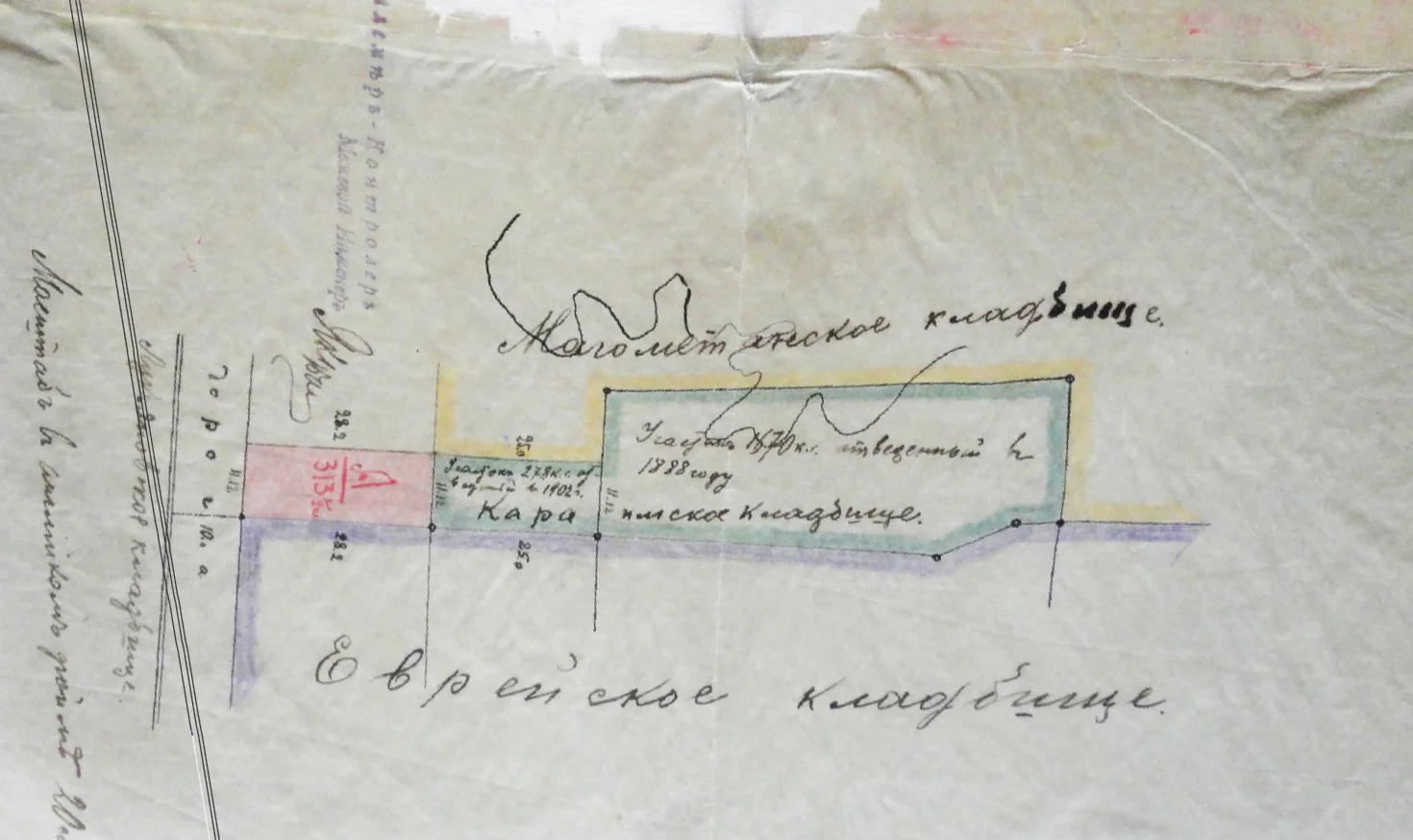

Both of the missiles landed on parts of the Babyn Yar territory where former cemeteries were located, as indicated by an allotment map from the late nineteenth century (see Fig. VIII).

The TV tower, hit in the first missile strike, stands on the ground of a former Russian Orthodox cemetery. The second strike hit what had been a Jewish cemetery, which also included sections for Muslims and Crimean Karaites, attesting to the rich cosmopolitan character of Kyiv at that time.

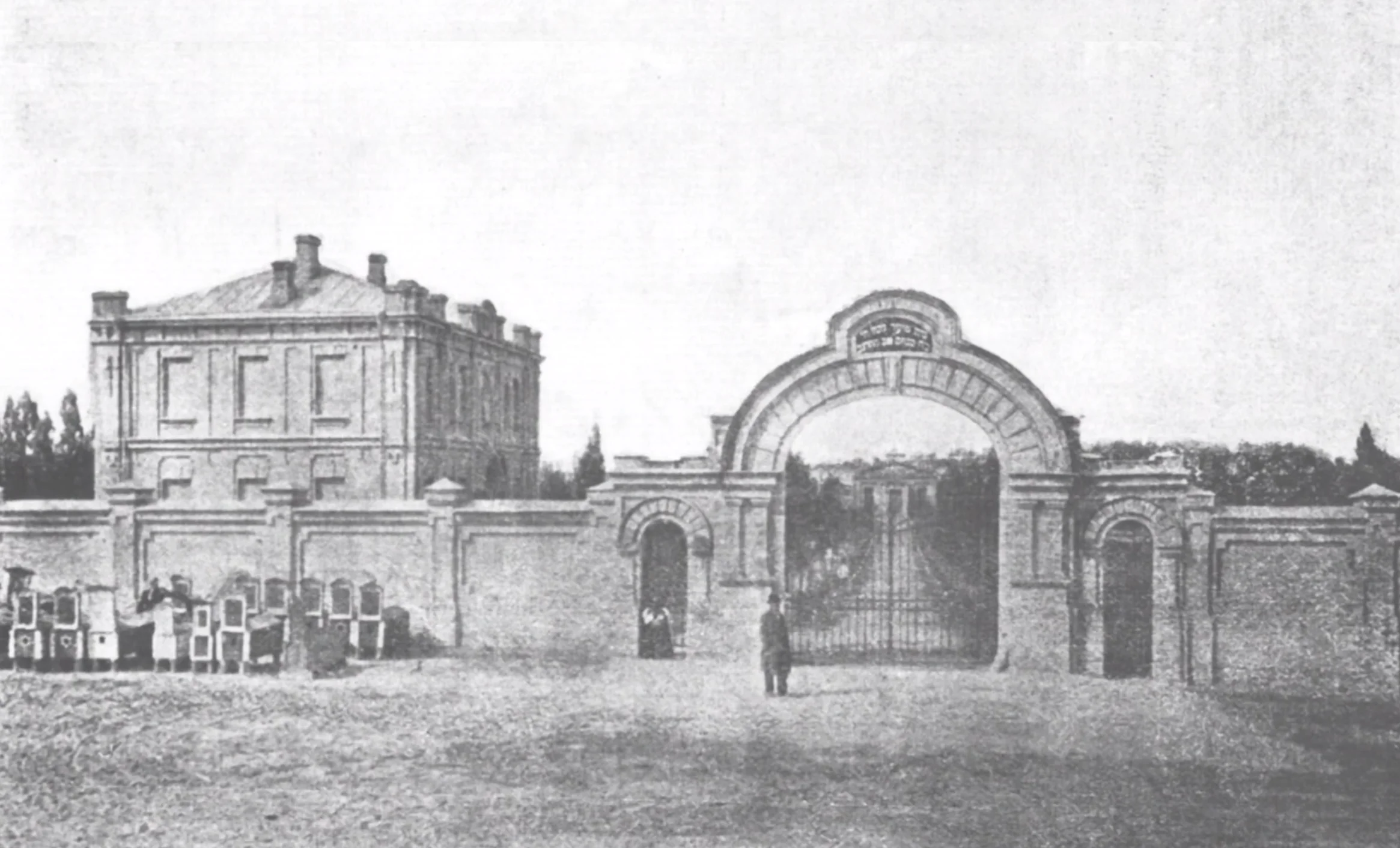

The official allocation of land for a new Jewish cemetery came about as a result of a decision from the Kyiv City Duma in March 1891. The following year, the famous Kyiv-born architect Volodymyr Nikolayev drew up plans for the layout of alleys in the burial grounds, as well as the creation of a brick wall with a gate and three auxiliary buildings.

At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, the territory of the cemetery was significantly expanded. By the end of the 1920s, the cemetery had reached capacity. During the 1930s, the state policy of persecution of religion in the USSR led to the vast majority of burials being deprived of religious rites and placement. In 1937 the cemetery was closed, and Jews were buried in various cemeteries around the city.

The gate of the aforementioned Jewish cemetery appears in the background of a piece of CCTV footage that captured the strike on the TV tower, allowing us to place it within the Babyn Yar site. The same gate appears in a photograph from the summer of 1944, in which Soviet troops are seen leading German prisoners of war.

That same year and the year prior, the area around Babyn Yar ravine was photographed from the air by the Germans for intelligence gathering purposes. Analysis of these aerial images reveals anti-aircraft guns abandoned on the ground and artillery craters, traces of the Soviet recapture of the city from the Germans. These craters (marked in Fig. XIII) were directly adjacent to the site of the Russian strike on the Kyiv TV tower. Here we see Russian missiles targeting the same Ukrainian territory where almost eighty years ago, as part of the Soviet army, Russians and Ukrainians were together battling the German occupiers of Kyiv

The massacres of Babyn Yar

CST’s digital reconstructions of Babyn Yar made it possible for the first time to geolocate a series of historical photographs within the landscape, yielding new information about the function of different areas of the site and the changes to its topography caused by repeated efforts to eliminate evidence of the crimes committed there.

Using their topographic models, CST was able to identify the exact sites of the mass executions, as well as those secondary sites where various phases of the process leading up to them were carried out, including areas where the victims were ordered to deposit their belongings and strip their clothes.

Throughout the occupation of Kyiv between 1941 and 1943, approximately 100,000 people — Jews, Ukrainian political prisoners, Romas, Soviet prisoners of war, and psychiatric patients — were systematically murdered on the territory of Babyn Yar.

The first and best documented of the massacres—and also one of the first and deadliest mass shootings of the Holocaust — took place in the westernmost spur of Babyn Yar ravine over two days, on 29 and 30 September 1941. Over 33,000 Jews were killed by members of Einsatzgruppe C (task Force C), one of the German ‘death squads’ formed after the invasion of the Soviet Union. These units were made up of members of the SS, security officers and ordinary policemen. Under the command of Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, this group, was explicitly tasked with murdering communist officials and Jews in the occupied Soviet territories. Under German command, local collaborators assisted in various tasks.

The process of mass murder began at the cemetery gate on the northwestern edge of Kyiv, where the Jews of Kyiv were ordered to gather. As they approached the intersection of Dorohozhytska and Sim'i Khokhlovykh streets, they were forced to leave their coats and luggage on the roadside.

Figure XVI shows the location where they surrendered their luggage, just 280 meters from the present location of the TV tower.

The victims were then led to a former sand quarry, dug up in the late 1930s right between two large branches of the ravine system, on the western part of it. There they were asked to undress in full, and taken in groups to the westernmost branch of the ravine.

In this ravine, members of Einsatzgruppe C ordered the victims to lay on the ground or on top the bodies of the already murdered before being shot themselves. Witness testimonies mention six to seven layers of human bodies laid one on top of another.

While we know the 1941 mass execution of Jewish civilians took place in Babyn Yar, the exact locations of the majority of the other executions that followed are still unknown. Those executions could potentially have taken place within any number of other areas in the Babyn Yar site, particularly other branches of the ravine. As such, we cannot rule out that the branch extending just metres west of the sports complex might have been a site of some of these executions. This possibility is reinforced by its proximity to a main road (we know that these subsequent smaller-scale executions were carried out systematically, often several times a week, with victims summoned to the site or transported in vehicles).

Erasure of evidence

In 1943, as the Soviets advanced on Kyiv, the Germans ordered prisoners incarcerated in the Syrets concentration camp to dig up and incinerate the human remains of those murdered in Babyn Yar.

In 1951, eight years after the Germans left Kyiv, and six years after the end of the war, Soviet authorities ordered that the ravines be filled with liquid mud, a byproduct of brick production from a factory nearby, further flattening the topography of the site. Their stated motivation was to enable the growth of the city over the ravines and former cemeteries, but the erasure of the site of commemoration was also in line with the Soviet politics of memory that sought to undo the difference between different national tragedies and erase rather than face these dark blemishes upon the past.

Documents about the massacre were also classified, and activists seeking commemoration were prosecuted.

Afterword

With our analysis, we seek to establish a clear evidentiary record of the destruction and casualties brought about by the Russian strike on the Kyiv TV tower. Drawing upon the CST’s work, this report also addresses the history of violence and genocide that occurred on this site over the past century, now buried under layers of earth and rubble but brought once more to the surface by this recent attack.

With the Babyn Yar landscape having gradually been rendered a vast monument entombing unspeakable acts and repeated crimes, the CST’s topographical reconstructions of the site have made visible for the first time the collision of different disjointed events across time, bringing them into uneasy dialogue with one another. Revealed within the stratified historical layers of the site are Jewish, Russian Orthodox and Muslim cemeteries from the 19th century; ravines used as Nazi extermination sites in the early 1940s, collapsed in, then reopened and covered up once again by the Germans; those same ravines used after the first massacre to exterminate Romas, Ukrainian political prisoners and Soviet prisoners of war; traces of the 1943 battle for Kyiv; and attempts by the subsequent Soviet government to seal off the site and the traumas it bore witness to.

Critically, the history of the site is not only one of violence but of different practices of cover-up and negation. Negation here refers not only to the topographical practice of burying crimes beneath layers of earth, but also to the act of controlling the dominant message by interrupting the circulation and interpretation of news and personal narratives, isolating individuals and restricting unwanted solidarity. The recent Russian strike forms a new contemporary layer atop the existing historical strata, itself an act of violence but equally—in its attempt to affect the way in which the reality of the war is mediated—one of negation.

First in the series

This is the first case in a series of investigations FA and the CST will undertake on particular buildings and sites that have been affected by Russian strikes since the beginning of the war on 24 February 2022.

When Russian missiles hit Ukrainian cities, the world sees images of ruins. For many, this is the first time they are encountering cities like Mariupol or Kharkiv. Analyzing these ruins can indeed help establish the exact circumstances of each attack, but each of these places, much more than debris, were buildings and sites loaded with social, historical and cultural significance.

In undertaking our analysis we seek to foreground the experience of Ukrainians, and the richness of urban life, that these places sustained before the war; their beauty; the network of social relations, in which they are embedded; the depth and complexity of Ukrainian history, that can be uncovered by closely looking at each of these places; and the way Ukrainians have resisted different forms of imperial occupation and domination, throughout history.